Amidst a nationwide effort to increase whole-facility energy efficiency, mechanical systems rank high among the most critical areas of focus. Space heating and domestic hot water production account for approximately 42% of energy use in the United States.

For many existing facilities served by a hydronic system, the straightest path toward a smaller carbon footprint and the quickest ROI may be to upgrade the boiler plant from conventional (cast iron or steel) boilers to high-efficiency (modulating/condensing) boilers.

The upgrade may be driven by several factors, including customer preference, tax incentives, or local mandate. In most instances, the benefits include lower energy expense, quieter boiler operation, and increased space in the mechanical room.

There are, however, several factors that engineers, installers, owners, and facilities managers should consider before converting a hydronic system from a conventional boiler to a high-efficiency boiler.

Venting

The most common hurdle to overcome during a high-efficiency retrofit is boiler venting. Mechanical rooms are often in a difficult location with limited access and space. At times, this may require some creativity to get the vent installed within the requirements of the new boiler.

Masonry chimneys and existing steel venting cannot be re-used when installing a condensing boiler where a conventional unit had previously served. This is for two reasons.

First, many of the cast iron or steel boilers being removed from service are atmospherically vented, meaning that that the flue did not need to be sealed. High-efficiency boilers (and some conventional boilers) are designed for induced draft, meaning that the flue operates at a static pressure higher than the atmosphere in the boiler room. This means that the venting must be sealed.

Second, the heat exchangers in condensing appliances are so efficient that flue gases are cooler and can be vented in multiple materials if the manufacturers have tested and certified the appliances with each type of vent material. The common materials are stainless steel, polypropylene, CPVC, and PVC. The condensate is corrosive and will destroy other vent materials. Each appliance will have different venting requirements, so the installation and operation manual should be referenced before each job.

The use of plastic vent material includes additional considerations. Only specific adhesives may be used, and large-diameter CPVC and polypropylene can be more difficult to source in some regions.

Some local codes eliminate the use of PVC and CPVC completely, or at certain operating temperatures. It’s up to the installer to understand and adhere to local codes.

Many installers choose to sidewall vent condensing appliances because the equivalent length to the roof is too great, or there is no existing chase. Others prefer to vent through an existing chimney. Because of the caustic nature of condensate, the chimney must simply be used as a chase. If the chimney is straight, it can be lined with a piece of pipe. If it’s not straight, it can be lined with a polypropylene flex vent product.

Individual or concentric vent terminations are both acceptable, when properly installed. If individual penetrations are used to supply flue and combustion air intake, ensure that the pipes are installed according to a manufacturer specification to avoid recirculation of flue gases.

System Piping

When replacing a conventional boiler with a condensing boiler, it’s important to look at the existing system piping. Is the existing system a full-flow or primary/secondary layout? In terms of flow rate, the current system must offer what the new boiler requires. If the system can’t facilitate sufficient flow, it must be re-piped to accommodate the new appliance.

Not all condensing boilers can be installed with a full-flow piping arrangement. Even if permitted, full-flow systems can be problematic because multiple zones with different flow rates can make it difficult to maintain the minimum flow required at the boiler.

Primary-secondary arrangements can still present water flow issues, so installers must fully understand the requirements. Proper installation of closely spaced tees is critical. The system circulator must pump away from the point of no pressure change, and the system flow must always be greater than the boiler flow.

System Cleaning

Cleaning a hydronic system before any boiler retrofit is good practice, but it’s especially important when converting from a conventional boiler to a high-efficiency boiler, or when the existing system includes old cast iron radiators or black pipe. This is because the channels within a high-efficiency heat exchanger are much smaller than those inside a cast iron boiler and are more likely to clog when decades’ worth of sludge is introduced.

Additionally, many high-efficiency hydronic retrofits include the use of permanent-magnet ECM circulators. These circulators are prone to collecting black iron oxide sludge around the wet rotor, causing early failure.

The best way to clean the system is to use a cleaning solution, like those produced by Fernox, Sentinel, or other hydronic water treatment brands.

Some installers prefer to circulate cleaning fluids and flush the system before the old boiler is removed, but this approach can be problematic because it exposes the entire hydronic system to the debris that was resting at the bottom of the cast iron boiler sections. It could settle in the system, especially if old cast iron radiators are present.

Other installers prefer to wait to flush the system until the new boiler is installed. This removes the dirt inside the old boiler, but now exposes the new boiler to all the dirt that had been dormant within the system piping and radiation.

The best way is to either isolate or move the existing boiler, introduce cleaning additive, circulate, and flush. After the system has been thoroughly flushed, the new boiler can be installed.

Keep in mind that the age and size of the system will determine how long it takes to flush the system. Old black pipe and older radiators will take longer to clean than a newer system with copper pipe and fin tube radiators. If the system was not properly maintained and had excess air, metal within the system has likely corroded. In this scenario, a shocking amount of dirt could be moving around in the piping or settled out in radiators or terminal units.

It’s also good practice to install a magnetic separator in a high-efficiency hydronic system, especially a system that has been exposed to black pipe or cast iron components. As previously mentioned, this will protect the boiler, circulators, and other system components from black iron oxide sludge.

Condensate Disposal

Condensing boilers generate flue gas condensate as a byproduct of efficient combustion. It occurs when flue gas temperatures reach or drop below 130°F or 135°F. This fluid has a pH range of 3.2 to 4.5, making it acidic. Where the condensate line is terminated must be considered due to its corrosive effect.

In rough numbers, condensate is produced at .75 gallons per hour per 100,000 BTUs of gas fired capacity. Anything downstream of the mechanical room can be damaged, including drains, cast iron sewer lines, and on-site septic systems.

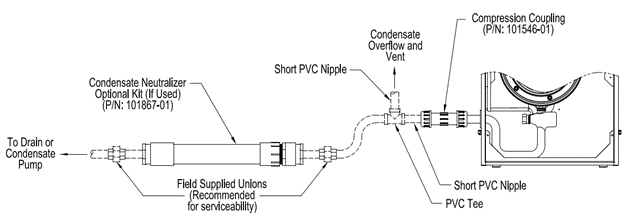

As a result, flue gas must be neutralized by a properly installed and maintained neutralizer and disposed of via a drain. Depending on the location of the boiler, a condensate pump may be needed in addition to the neutralizer.

Gas Supply

It’s considered best practice to replace the existing gas regulator when converting a hydronic system from conventional to condensing technology.

Older regulators may not be able to facilitate the changes in gas pressure as a result of modulating burner turndown ratios. In some instances, old regulators can’t adjust rapidly enough and could potentially create gas supply issues.

With the introduction of turndown ratios above 5:1, the industry learned that not all regulators respond the same. There are lock-up and non-lock-up type regulators. Lock-up type regulators are very effective at eliminating spikes in gas pressure, but these units can also have slower response times, creating problems for modulating burners.

Some gas valves won’t open if there’s too much pressure. A utility line gas pressure spike could result in a no-heat situation. Also, some regulators don’t respond rapidly enough to provide the gas pressure needed by the boiler as it quickly modulates up.

It’s critical to follow the instructions supplied with a new regulator, especially the vent line sizing. Some regulator manufacturers require an increase in the vent line diameter as lengths increase.

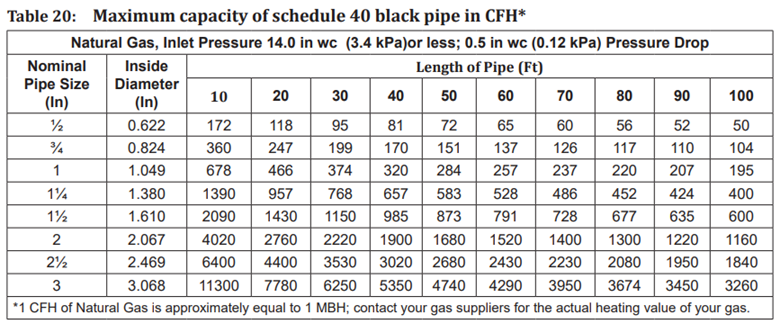

Always reference the correct chart in the National Fuel Gas Code (NFGC) for gas line sizing. Never assume the connection size on the boiler will work for each job. Static and dynamic gas line tests are best practice before any retrofit and are definitely the first thing to be checked if there are ignition issues or loss of flame.

Return Water Temperature

Over the years, it’s amazing how many times I’ve heard that a high-efficiency boiler retrofit didn’t yield the energy savings that was expected. In these scenarios, the reason is always the same. The problem in this scenario is that the return water temperatures are too high to permit condensation of flue gases. If condensation never occurs, the savings potential will never be achieved.

Whether return water temperatures are low enough depends almost entirely on the amount and type of radiation installed, relative to the heat load of the space. Return water temperatures should be roughly 130°F for proper condensation.

Without heat emitters that provide low enough return water temperatures, a high-efficiency condensing boiler will operate at similar efficiencies as a cast iron boiler. That said, the condensing boiler has the advantage of firing rate turndown, which could be enough benefit without the unit operating in condensing ranges.

Modulating-condensing boilers are no longer new technology. They’re increasing in popularity due to customer demand and as a result of efficiency mandates.

These appliances are not difficult to install, but there are a few additional considerations when preparing to install a high-efficiency boiler in place of a conventional boiler. Luckily, these retrofits become business as usual for installers after one or two projects where best practices were followed, and all considerations are taken into account.

Dan Rettig is the product manager for Thermal Solutions, a subsidiary of Heating Solutions Sales Co. Rettig‘s career began as an HVAC commercial service technician focusing on chillers, cooling towers, heat pumps, boilers, and oil burners. He also has experience with multiple control platforms for building integration. Over the last 13 years, he’s been employed by two different boiler manufacturers, including 12 years in product management. He holds a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering and an associate’s degree in heating, ventilation, air conditioning, and refrigeration.